Killing vowels and milling fonts

Apr 24, 2024, type | telugu | langauge | research |

This piece of writing will focus on writing systems that use non-Latin scripts and the complexities of producing fonts for them. By delving into the history and evolution of writing and modern forms of standardisation, it tries to give an overview of some of the apparent and not so apparent challenges in type making. It does so by comparing Latin script with Telugu script from South India. As there is a consistent Latin type design and font making this text, in its capacity will try to be a useful resource for fellow design students and enthusiasts in understanding font making for non-Latin scripts. It is important here to note the difference between font making and type design. Font making is about the production of fonts which can in turn render a designed typeface. Fonts are devices that enable reproducible communication. They are made to ensure that each letter of a script acts in synchronicity, to solve a problem of printing or spaces or to provide an extra layer of meaning when necessary. The word font, as clarified by many before me, is a term referring to a set of physical objects that embody letterforms, symbols, numbers. These objects are sorts in movable-type printing, film strips in phototypesetting or font files on computers.

The font (“fount”) is the source of the typeface. It is the object that makes possible the reproduction of identical copies of the words in The Bible or the echoing of “Hello world” on HTML webpages. The font (the collection of metal blocks or a font file on a computer) is not always a direct result of a single type designer. The graphic designers of today seldom participate in the making of fonts as they are mostly involved in typeface design. Historically, the design of a typeface had to be carved into metal letter blocks by a black smith in the varied sizes specified by a designer. In modern-day type design software, one can start drawing letters directly into the programme, and if need be has to be coded by programmers to act in a specific way with the keyboards of personal computers. The smiths and programmers who have concerned themselves with typefaces have developed specific knowledge related to font production. This involves the usage of materials both physical and digital and the understanding of writing systems, scripts, languages, publishing technologies and culturally specific needs.

I believe that the craft of type making is script-agnostic. It tries to rationalise letters and characters. There are various categories of writing systems associated with different languages. They are characterised by their relationship to the sounds formed. The most popular language, English, uses an alphabet-based script. Since their inception, computers have been made in English, and as a result they make it easy to produce fonts for and to typeset Latin scripts. But certain scripts pose challenges that need to be solved based on their typesetting and cultural requirements.

Latin script (as used for the English language, among others)—leaving aside for the moment quirks such as silent letters and an odd letter, c, with two kinds of sounds—is the basis for a system of writing where placing consonants and vowels side by side achieves various sounds. Consider the word pa. Placing the letters p and a side by side produces an elongated sound; the life of the sound uttered when the letters are read together is longer than the respective sounds of the individual letters. Now let’s put the letter r between the said letters p and a. The outcome, pra, takes the same amount of time as pa to utter, but the tongue riffs and changes the character of the initial sound. Visually, too, the letters occupy more horizontal space on the baseline. This stacking of letters, one after the other, gives English writing (Latin script) a unique character. It allows for fonts to be easily produced, both in metal and digitally, for individual letter forms to be rationalised, and for the script to act as a universal phonetic system. Such a writing system is categorised under the alphabet. This makes it easy to teach type design, with the Latin alphabet serving as a basic building block for understanding type.

The organisation of an abugida or alphasyllabary is a bit more complicated than the simple horizontal stacking of letters to achieve meaning or sounds. Consider Telugu, a Proto South-Central Dravidian language descended from Brahmi. It uses Telugu script, an abugida. It originates from South India and resembles the Kannada language.

An abugida script consists of base characters (vowels and consonants) and diacritics (vowel markers). The consonants possess an inherent vowel that can be muted or changed by the diacritics. Two or more consonants combine to form conjunct consonants. The word pa is written with a single character, ప. In Telugu a base consonant has an inherent /a/ sound represented by the tick-mark above (Thalakattu). The character sits on a baseline just like an English letterform. To achieve pra, the letterform r (ర in Telugu) has to be introduced under the initial letter ప్ర (pra). In this case, the ra (ర) doesn’t occupy horizontal space as it would in the Latin alphabet, but gets stacked under the first consonant and also visually looks like a crescent moon. Telugu consonants when forming conjuncts take completely different forms from their standalone representation and are called Ottulu. Now to see how vowel marks affect this unit of text. Let’s make the character praa. The vowel mark ా (ఆ, /aa/) modifies ప్ర (pra) to ప్రా (praa) replacing the tick-mark (Thalakattu). The rest of the vowel markers modifying the character ప are as follows: పి (pi), పీ (pii), పు (pu), పూ (puu), పె (pe), పే (pee), పొ (po), పో (poo), పై (pai), పౌ (pau), పృ (pru). Vowels retain their original form when used in initial position, otherwise they each have a diacritic to change consonants and conjunct consonants.

An abugida writing system employs a virama. This is a mark found in Indic and other Brahmi scripts to suppress the inherent vowel of the consonant to which it is applied, leading to a dead consonant. It is popularly known as a vowel killer. In Telugu it is called pollu and is written in Telugu as ్. The vowel killer mutes the inherent vowel of the letter, so ప (pa) when written with ్ (pollu) produces ప్ (p), a dead consonant. The resultant sound is devoid of a vowel.

To stack a consonant under another, the vowel killer needs to be typed before the second consonant. The vowel killer acts like a shift key, letting us access hidden symbols in the keyboard. When typing a virama, the consonant loses the vowel and gets modified by other consonants (e.g., pra, ప్ర). This is not as apparent in written Telugu. Generally speaking, the consonant and vowel marks work in this fashion when typed: consonant + vowel → syllable. This can be seen in the following examples:

- ప + ఈ (ీ) → పీ pa + ii → pii

- ప + ఉ (ు) → పు pa + u → ju

- ప + ్ + ర + ఊ (ూ) → ప్రూ pa + vowel killer + ra + uu → pruu

A Telugu script with all the rules of spelling and character sequences might require the designing of 600–700 characters. With multiple modifier keys like shift, alt and virama, hundreds of glyphs are accessible even when using a Latin keyboard. This is how people using scripts completely different to Latin use Latin keyboards to type. While typing, every person is sorting through a set of sorts just as a typesetter using movable type. This is made possible by a technology called Unicode. It is an attempt at standardising a way to encode text in order to store it, send it and process it.

Computers do not understand natural languages such as English or Telugu at face value. They need intermediary processes. All natural languages must be made into patterns and sequences that a computer understands. Unicode is such a sequence or a system. In Unicode, every letter has a designated code point, making it easy for the computer to understand and store individual human-readable glyphs. The Unicode technology has made it possible to standardise digital font production for existing and endangered scripts. In a nutshell, Unicode works as follows: every language is provided with a locale that defines the language’s environment, such as the glyphs and keyboard input. When the English keyboard is chosen and the character A is pressed, a code of 65 is passed to the computer. The same happens with Telugu, but A is mapped to అ and a decimal code of 3078. An application such as MS Word receives the keystroke and lays off the text in a proper way.

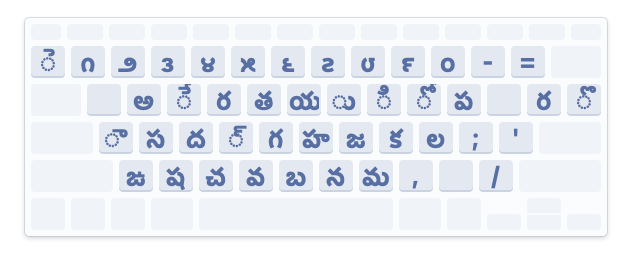

To understand a script that is prevalent and standardised by the Unicode consortium, activate the keyboard of that script on your computer to play around. These keyboards are built in programmes that change your physical keyboard to type in other languages. They are shipped with your operating system. They give you the ability to type the characters and observe how the ligatures work with key bindings.

The Keyboard from MacOS Telugu QWERTY

Knowing thousands of decimal codes for individual glyphs can’t help designers to make typefaces. OpenType shaping engines in our computers make it possible to read font files. A designer has to meticulously create the features necessary for a typeface to render. The feature file is situated inside the font files. It contains information about a typeface’s formal properties. To list a few: the position of glyphs in relation to other glyphs, marks that need to be replaced by others, letter combinations that need substitution with ligatures and information about spaces between letters (kerning), etc. This information helps a typeface to be rendered as envisioned by a designer.

Inside every font design programme such as Glyphs or FontForge there are functions to add these features. One can populate these tables using a human-readable format, making use of certain syntax and specific names given to the glyphs during the design process. An example of such a feature file for a Latin font looks like this:

# Script and language

languagesystem latn dflt;

# Ligature formation

feature liga {

substitute f i by f_i;

} liga;

In the above example, we specified language and script to let the computer (OpenType shaping engine) know that the font uses a Latin keyboard. We then specified a feature that reads: when f and i are typed, replace them with fi (a composite glyph) by finding it in the font file. More substitutions can be populated in the same parenthesis.

The same logic applies to Telugu too. But instead of ligatures (ligas in OpenType syntax), the Telugu forms that change above the base character are called Above base substitutions (abvs). We define the language system, add a feature abvs, and then add a rule to substitute ప (pa) with పి (pi): ప (pa) + ి (vowel mark of ఇ, i) → పి (pi). To achieve పి (pi) the abvs feature is used in the feature table:

# Script and language

languagesystem telu dflt;

#Above base substitution information

feature abvs {

substitute pa i by pi;

} abvs;

There exist many more features to achieve a rendition of more characters. In the case of a conjunct consonant ప్ర (pra), more steps need attention. The user with a Telugu keyboard enabled types pa, halant (vowel killer) and ra. The programme looks for pa + halant, which is a dead consonant: ప (pa) + ్ (halant) → ప్ (p). The feature is written as:

# Script and language

languagesystem telu dflt;

# Ligature formation

feature haln {

substitute pa virama by p;

} haln;

Note that for this substitution every character being specified above has to exist in the font file. A dead consonant also has to exist in the designed type. Once the pa + halant (p) is found, the programme looks for ra. As discussed before, a dead consonant is easy to transform into a conjunct consonant. Instead of being substituted with the base consonant form of ra, it has to use the crescent moon form of ra under pa. The rule to replace p and ra with the conjunct pra works this way:

# Script and language

languagesystem telu dflt;

# Ligature formation

feature cjct {

substitute p ra by pra;

} cjct;

This is a way to make rules and simple conditions. True, it is a programming language for defining the properties of the characters in a font file. This means the above examples are not strict but can be solved in a way that is needed by the typeface. One can find resources regarding syntax on the internet. This is just an overview of a technology that lets us make fonts regardless of a script’s complexities.